As someone who has only read “The temptations of doctor Hoffmann”

The New York Stories is also not my first Hardwick discovery. I tend to discuss literary legacies once I can compare two works or stages of an author’s career. If they turn out to be completely different—almost nemeses to each other, as if the author’s psyche had been split in two—that’s when the need to talk about them arises.I also find it interesting to engage in a critical exercise at the beginning of a reading: to compare the first impression with the final one. This allows us to see whether our convictions hold firm or, on the contrary, waver to give way to a second opinion—one that is more complete and, hopefully, more accurate.

Some time ago, I read Seduction and Betrayal: Women and Literature, a marvelous study of female writers such as Emily Brontë, Zelda Fitzgerald, and Sylvia Plath. It offers a profound insight into the minds of these exceptional artists, where Hardwick’s subjective yet sharply critical voice makes the reading an effortless pleasure. Similar to the effect of an off-screen voice, the author’s unbiased discourse guides us through the intimate experiences of each artist without compromising the literary quality of the work.

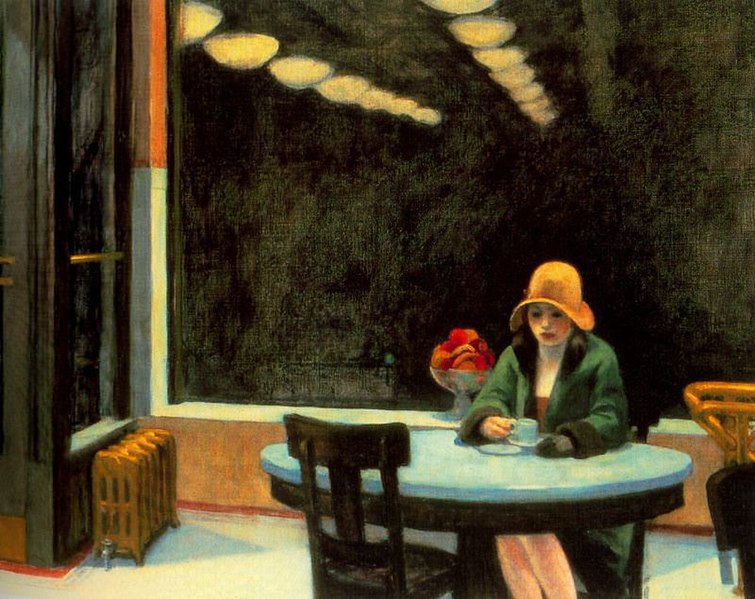

But if the subjectivity that permeates Seduction and Betrayal helps bridge the gap between reader and writer in a unique way—bringing them together in a sort of salon where a dialogue unfolds, though neither side speaks, only listens—then, in The New York Stories, quite the opposite happens. Paradoxically, this same subjectivity hinders the narration of Hardwick’s personal experiences.

In this second volume, published in Spanish by Navona, the reader encounters once again Hardwick’s cultivated and brilliant reasoning, but here it feels diluted by an implicit sense of shame or insecurity that distances her from the sharp observations she applies to her literary predecessors. It is as if, when dealing with her thinking or reasoning, Hardwick were unable to approach events with the necessary objectivity to capture them fully in that first act of writing. Although this reflection stems from reading only one of these New York stories, which aims to bring her work to a wider audience, the lack of narrative force is enough to discourage the reader from delving further into the text.

It is as if she were asking aloud: Where do I stand intellectually in the world that unfolds around me?—yet she cannot seem to find the right answer.

With a trembling hand, she narrates the relationship she formed with a family who lived in the same building as her, particularly with the father, a theology professor around whom all the other characters—including herself (or at least the character she projects)—revolve. Despite her presence, the narrator carries the weight of an observer: a witness to the family’s disputes and to the inner conflicts that surface in Dr. Hoffmann’s personality.

It seems Hardwick’s intention is to make an intellectual statement and take a stance on the classic thematic dichotomy of religion versus atheism (or perhaps more accurately, atheism in front of religion). This idea is reinforced by the role of the narrator’s former class partner, a minor character who serves as a vehicle for her reflections on Dr. Hoffmann and his apparent religious malleability. However, this statement ultimately gets lost in a tangle of paragraphs and superfluous lines describing the life of the family she observes from a distance.

Even if I am initially disappointed by what The New York Stories seems to offer, I believe that the initiative to publish Hardwick in spanish (and, hopefully, soon in catalan) is both timely and relevant—an effort led by a team with a finely tuned sensitivity. Recovering literary figures who may have been overlooked outside their country or region of origin allows for fresh perspectives on works and themes that have been examined to exhaustion, offering both the general public and the field of literary research a true breath of fresh air.

Hardwick’s approach to the works of the writers whose lives she explores in Seduction and Betrayal, as well as the dialogue she establishes with other literary figures who, like her, engage in the same endeavor through their own methods—paving the way for future scholarship—opens the door to new, yet unexplored conversations.